This innovative experiment called “online skill-ups” was designed by participatory educators. As such, we were challenged by the question: how do we teach people skills using computers at a distance?

From the beginning, we knew that such a groundbreaking approach to teaching needed a new name. This is not a training. Or a course. Or a class. Those are real terms and we’d like to preserve their meaning — working online both frees us and limits us. We reflect that with a new term that represents our vision — a place people go to get some new skills: Online skill-ups.

The limitations

In practice, many of the interactive tools we wished to create this type of online learning experience do not exist.

For a while we experimented with simultaneous interactions. We love the idea that participants could interact with each other. But the foremost problem was the technical problem. While in some places video chatting could work, a poor internet connection would mean that someone else was left out, locked out, and further marginalised.

There were other challenges: timezones, language, moderation, and infiltration. Any one of these could end up making the project a failure.

Also, we were aware that while there’s great benefit in interacting online, it’s a lot of coordination that should not be underestimated.

Because of our goals at 350, we had additional challenges: a global audience (limiting the scope of specificity to region) and a wide range of knowledge and experience levels (totally new to activism and climate change and some of the most experienced climate activists on the globe).

This left us choosing the structure we have now: someone can decide to take an online skill-up and learn anytime, anywhere at their own pace.

The advantages

Teaching in an online space also frees us up. It’s far easier to do a multimedia experience. People can set their own speed of interaction. We can create different pathways for learners – so they can pick the order of their own learning (and even skip sections they don’t want to learn about).

The biggest problem remained technical. Most of the online teaching platforms are based on out-dated notions of Western education. They offered “quizzes” and all questions had “right and wrong” answers. Most simply were one way experiences: someone sat, read, and if we were really lucky they got to click to see if they remembered what they were being told.

We were lucky that we connected with Elucidat. Their platform was easy to work with (a ‘what-you-see-is-what-you-get’ WYSIWYG platform) and their “quizzes” had the greatest flexibility matched up with ease of use.

Teaching online at its best has little representation to in-person trainings. But that does not make it unworthwhile. It can teach certain kinds of skills — with a preference towards hard skills that are knowable (versus soft skills that are intuited). And as the technology shifts, more may quickly become possible.

As we began building the sessions, we realised we had to re-think which skills we could transmit via the online skill-ups. Some skills are harder to transfer (doing a 1-on-1, for example). Others are easier (how to identify a target, for example).

One breakthrough occurred when we realised we can pose questions and, with some limitation, respond to their answers. The online skill-up Advanced Campaigning Lessons used a case study format that had people interact with a real life case and then get asked: “What would you do?”

The answers told us a lot about a person’s activist style and so, depending on the answer, we could provide specific feedback and coaching. All the while, they could see what worked (or didn’t work) in real life.

Our goal was to keep growing on people’s strengths, helping them identify their own brilliance and marking their own tendencies to support self-awareness.

Our pedagogy

The world of “online training/courses” is dominated by boring lectures, one-way questionnaires, and drawing out the worst of traditional education. We don’t want to replicate that model — but we are honest enough to have grave reservations about what can be doing in an online platform.

When we mean the worst of traditional education, a big part of what we mean is what Paulo Friere long ago called the “banking” model of education. In that model, the “learner” is an empty vessel.

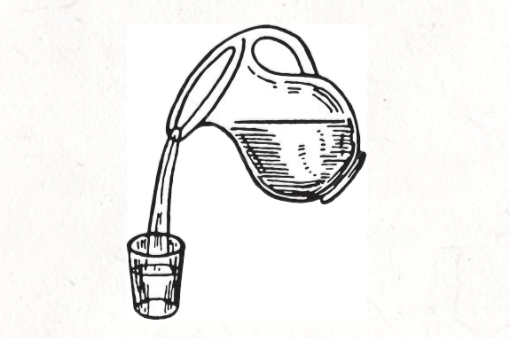

The role of the teacher is to fill up the empty vessel with their knowledge. Through lectures (or videos, or reading) the teacher fills the learner with what they should know. The creative teacher may use other methods, even participatory ones, but the end goal is always the same: transferring information from the teacher to the student.

The role of the teacher is to fill up the empty vessel with their knowledge. Through lectures (or videos, or reading) the teacher fills the learner with what they should know. The creative teacher may use other methods, even participatory ones, but the end goal is always the same: transferring information from the teacher to the student.

The teacher can then find out how much knowledge the learner has absorbed, through testing and even the use of questions. The student who gets the right answers is the one who can repeat back what the teacher taught.

This is the danger of online training courses: most online courses have been built on this assumption.

Activist education cannot be effective with the banking model. We need people who think for themselves, use the culture and language of those around them for justice, and develop indigenous approaches and methods.

So if the “banking model” — with its one-way exchange of teacher and student, what is the alternative? The Elicitive Model.

The elicitive model sees that living has given the person experience. The person brings expertise from their job, their love life, their relationships with people, their struggles and successes fighting structures and systems, their paying taxes or buying groceries.

Instead of the teacher filling them up, the elicitive model is about sharing the knowledge amongst each other — the teacher included. The teacher will learn alongside the students, who explore their own histories and backgrounds, as each individual finds their relationship to the material being taught.

Instead of the teacher filling them up, the elicitive model is about sharing the knowledge amongst each other — the teacher included. The teacher will learn alongside the students, who explore their own histories and backgrounds, as each individual finds their relationship to the material being taught.

Our goal in these training courses is to strive for the elicitive model. Each online session we attempted to connect our content with something from people’s past experiences. We did this to honor what they were bringing, encourage self-awareness, and provoke questioning of our material.

There are limitations of technology and the lack of engaged listeners in online platforms. Therefore we are not so bold as to claim that we are doing the elicitive model — we honor what elicitive means too much. Instead, our goal is to be in the elicitive model as far as we can go.

Two models of education

The Banking Model

- is a transfer of information solely from the teacher to the student;

- ignores culture and therefore treats the Learner as a recipient of whatever knowledge comes there way;

- is measured by whether the student “accurately” (i.e. uniformly) parrots back what the teacher says;

- cares more about teaching content than about teaching people to think for themselves.

The Elicitive Model

- starts its departure from the knowledge and experience of the student;

- values culture and sees it as a resource for all the Learners to learn from;

- is measured by how students integrate the knowledge into their own worldview values application of the material — even if it’s different than the teacher’s intent;

- is about empowerment.

How we attempted to apply this

Here’s an example of a session and how we attempted to redesign it based on the elicitive model.

| Teaching Concept | Traditional Banking Model | Elicitive Online Skill-up Model |

| Campaigning | Give out a bunch of definitions: what is a campaign, goal, target, tactic

Take questions, give answers that clarify the definitions Ask people to get in groups to pick a goal and a target Tell people where they are right or wrong |

Ask people to think about a time when you got someone to do the right thing — even if they didn’t want to do it

Have people shared what they did, see how others responded to that question Describe campaigns as an example of that — use their story to explain what a campaign is Tell stories that draw out different elements (like having a focus, targets, etc), inviting people to reflect along the way in what they see |

| Divestment | Give a PowerPoint presentation with vignettes and examples of Divestment, including pillars of support it is taking on

Take questions, give answers Test people on how much they understood from the presentation. Grade people on how much they got |

Start with a metaphor of Divestment that can connect to people’s lives

Ask people to do a power analysis of the fossil fuel industry (using the pillars of support): what pillars do they see? Share how the Divestment movement is taking out one of those pillars Give some examples of targets the Divestment movement has done Ask people if they were to create a Divestment campaign they might want to pick: offer examples from the past and share what others came up with (etc) |

In conclusion

We are aware this is an experiment. As with all experiments, others will come along with critiques and improvements. We welcome those.

At the same time, we encourage others to abandon the use of phrases like “online training” as we are really dealing with a new creature. Let’s keep pushing the builders of technology and stretching ways to reach our goal of activist empowerment.

For now, let’s close with the challenge from Paulo Friere’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed:

“…the fact that certain members of the oppressor class join the oppressed in their struggle for liberation, thus moving from one pole of the contradiction to the other… Theirs is a fundamental role, and has been throughout the history of this struggle. It happens, however, that as they cease to be exploiters or indifferent spectators or simply the heirs of exploitation and move to the side of the exploited, they almost always bring with them the marks of their origin: their prejudices and their deformations, which include a lack of confidence in the people’s ability to think, to want, and to know. Accordingly, these adherents to the people’s cause constantly run the risk of falling into a type of generosity as malefic as that of the oppressors. The generosity of the oppressors is nourished by an unjust order, which must be maintained in order to justify that generosity. Our converts, on the other hand, truly desire to transform the unjust order; but because of their background they believe that they must be the executors of the transformation. They talk about the people, but they do not trust them; and trusting the people is the indispensable precondition for revolutionary change. A real humanist can be identified more by his trust in the people, which engages him in their struggle, than by a thousand actions in their favor without that trust.”

– Daniel Hunter (Jan 2018)